“It is our inward journey that leads us through time—forward or back, seldom in a straight line, most often spiraling. Each of us is moving, changing, with respect to others. As we discuss, we remember; remembering, we discover, and most intensely do we experience this when our separate journeys converge.”

ONE WRITER’ S BEGINNINGS, Eudora Welty

Introduction

Female, But…

She was the only daughter of Italian immigrants, another girl child, Margherita, having died at birth nearly twenty months earlier. Squalling onto the white, metal-topped kitchen table the family still uses, Pasqualina Donnarumma came into the world nine years before the Great Depression, on January 24, 1920. Like her girl cousins and paesane, other women whose ancestors migrated to Connecticut from her father’s Frigento, in Campania, and her mother’s Tolve, in Basilicata, my paternal aunt grew between two worlds, the customs and expectations of one often conflicting with those of the other.

How could she realize her dream of a fashion career in New York City? What skills would she need to negotiate the “great divide” between domestic expectations and the public marketplace? Who would mentor her as she ventured from sink and stove to showrooms and runways? Where might she develop her desired self?

The identity Zia Pasqualina sought existed beyond the boundaries of gender definition within her tribe. Wife, Mother, Virgin, Whore—clearly delineated and understood female personae—were too narrow, too idealized or demonized to contain her various, sometimes contradictory personal traits. She needed a larger dictionary, more nuanced identifiers to begin to imagine, let alone develop, a self that could bridge two continents and escape the ironic constraints of her mother, who at thirteen had herself set off independently from her tiny village for a new life in America.

Pasqualina’s initial disobedience of my grandmother’s admonition not to leave Ward Street but for the necessities of church, school, and grocery, led to a fulfilling, five-decade career that transformed her parents from renters to owners, sent her brother, my father Carmen, to Fordham and Columbia Universities and a successful college-teaching tenure, and dressed a generation of four nieces and nephews. Her training as a buyer of Better Women’s Sportswear, under the tutelage of the formidable and generous Beatrice Fox Auerbach, owner of G. Fox and Company, in Hartford, Connecticut, not only changed her wardrobe from cotton housedresses and aprons to fine wools, silks, and linens, but also proved to me without a doubt that a daughter of struggling immigrants could excel at valuable pursuits besides the domestic.

Unlike my grandmother and mother, my aunt was not consumed by husband and children. People of note in the business and social realms of our small state considered her financial acumen and sense of style valuable enough to pay her well. She dressed the archbishop’s nieces, organized wardrobes for the wives of Hartford’s insurance executives, hosted fashion shows at country clubs to which our family would not have been admitted. She spoke and wrote as if she had attended college, so diligently did she read the New York Times, Women’s Wear Daily, Vogue, and the many books my father brought into the house. Financially independent, she lavished us with clothing, decorated the family home, and took vacations alone. We were not to disturb her when she predicted next season’s figures on the dining room table. Her work was deemed important, as if it were my father’s, as if it were a man’s.

Still, Zia Pasqualina spent nearly every Sunday of her life at the family home in Waterbury, Connecticut. She came to Mass with us, prepared the meals with her mother, Nonnie, and mine, Louise, and, despite the availability of an automatic dishwasher, soaped the dishes by hand after the extended family’s midday meal. Later in the afternoon, she drove us to visit her cousins Lucy Pesino and Peggy Albano or one of “the Becce girls.” With them, she spoke of her work at the store, her trips to Manhattan showrooms, the next season’s fashions. I listened, becoming more and more aware of a colorful, competitive world beyond the secure embrace of those who shared our blood.

Besides Connecticut’s onetime Governor Ella T. Grasso, the members of the Congregation of Notre Dame who taught me in secondary school, and celebrities and writers whose lives exceeded the conventional bounds of our family and neighbors, my aunt was the only other woman I knew during my formative years whose adult identity developed from an outer professional life. Despite her prowess with a broom and refined cooking and laundering skills, no one ever thought her a housewife. Since her job was in Hartford, some thirty miles away from home, no one questioned her solitary ability and need to drive a sporty car or to use bus and rail and flight for business-related travel. When she went to the market, she did so without a list of necessities, but rather with a hunger for luxuries—pearl onions for the cocktails she and my father drank before dinner, thin asparagus for a frittata, seltzer water she flavored with oranges, lemons, limes. Each February, when she took a week off, she did not visit family in Boston or New York, but instead flew to the sun of West Palm Beach. And when she dressed, there was no mistaking her style—her signature dyed-black hair with its purposeful streak of silver capped the elegant, finely-constructed wardrobe she maintained with military precision.

I followed her like a stalker, consistently devaluing my mother and grandmother. They cooked, cleaned, and ironed every day–Nonnie a confident commandant, Mom her mother-in-law’s junior officer, ready and near, never hovering, always available. No matter what they were doing or the time of day or night, I always felt free to interrupt, to take them away from their tasks and themselves. Still amazing to me now is that they always responded immediately, the great majority of the time with outward willingness and tested calm. They were the selfless framework holding the rest of us up. Essential, gifted, and underappreciated by me, they allowed the rest of us to flourish. Not until I left for college did I recognize the magnitude of their work.

Instead, ignoring their necessary, repetitive machinations, I sat beside my aunt as she penned her orders every Monday, the day G. Fox and Company was closed. While she decided between cashmere or merino, Bermuda shorts or capris, I drafted my first stories on yellow legal pads close to her. Both of us sat like company at the dining room table, the place where men usually lingered while the women toiled in the kitchen. White, cool walls, thin strips of wood bracketing flocked brocade, a chandelier glittering above the table for twelve where we both splayed our papers. When I read Virginia Woolf in college, the author’s inheritance from her aunt and a room of her own reminded me of us.

As a writer whose craft requires solitude over long expanses of time, I think of the three women who raised me: How two of them devoted themselves completely to family and home, and the third stepped further afield, testing her traditions and her relationships, and showing me a way between them.

I wonder how lonely she was or she wasn’t in the hotels in New York, on her stays in Florida, in the apartment she kept in Providence for the six years she worked at The Outlet Company, in California, in Paris, Rome. Did she miss us? Or did she embrace the hush, listen to a ticking clock, linger over a supper she cooked or bought to suit only herself? Were there men or women we didn’t know? Escapades, triumphs, disasters? What was her life of the mind when she was not the butcher’s daughter, the professor’s sister, but herself, Pasqualina, Lena, Lee?

Poet Mary Oliver’s words resonate:

“When it is over, I don’t want

To wonder

If I have made of my life

Something particular, and real.

I don’t want to find myself

Sighing and frightened

Or full of argument.

I don’t want to end up simply

having visited this world.”

When I stayed with her in Providence, Rhode Island, one weekend in the late Seventies, we walked from the Regency Apartments by the police station to The Outlet’s anchor store. The cop on the beat winked, “Hi, Lee,” an old woman on her cane near the cathedral stopped to chat. The phone message on her desk read, “Let’s have dinner, Adeline.”

She had a second life apart from the family that none of us shared. She could exist and thrive outside the tribe. This singularity made her compelling to me. It showed me that possibility was no mere abstraction, but an energy thrusting me forward toward the titillating unknown, my own future taking shape. Eagerly imagined. Sought.

Writing is that part of my life—the self-conscious activity of questioning, exploring, leaping into the light, searching for the yet-to-be-discovered. Perhaps it is no accident that, one by one, pieces about her found their way to publication first. Does she know, now, when I tell her? Alzheimer’s has turned her into a secret, many secrets I want to uncover. Still, I watch her in her hospital bed, waiting in the silence that is now our constant companion, to catch some meaning from her face. To hear some final word from her who, until she could no longer speak, I realize had been my most trusted oracle.

When I was a child, she told me she had looked to variants of her name to craft her American self. Lena Horne, Lee Remick, Peggy Lee. But even the staff at The Lutheran Home in Southbury, Connecticut, where she still breathes, knows her at “Auntie Lee,” the name my mother tells me she uttered the moment I was born, the name by which for over fifty years she identified herself to all comers. An unimaginable gift. Unsought, unnoticed, until she could no longer utter it. So I will say it for her. Auntie Lee. Zia Pasqualina. Not my mother or sister or cousin or friend. But the woman who formed and nurtured my aesthetic sense, who taught me that contradiction is as likely as confluence, and who convinces me still that our aunt-niece relationship bridged the gap she thought at first a chasm. “Aunt” gave her a fifth option to be. “Zia” allowed her to separate and belong. It is that duality that informs my story.

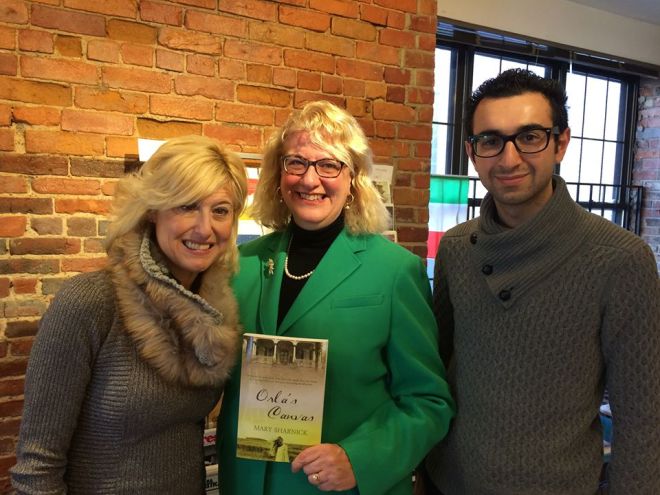

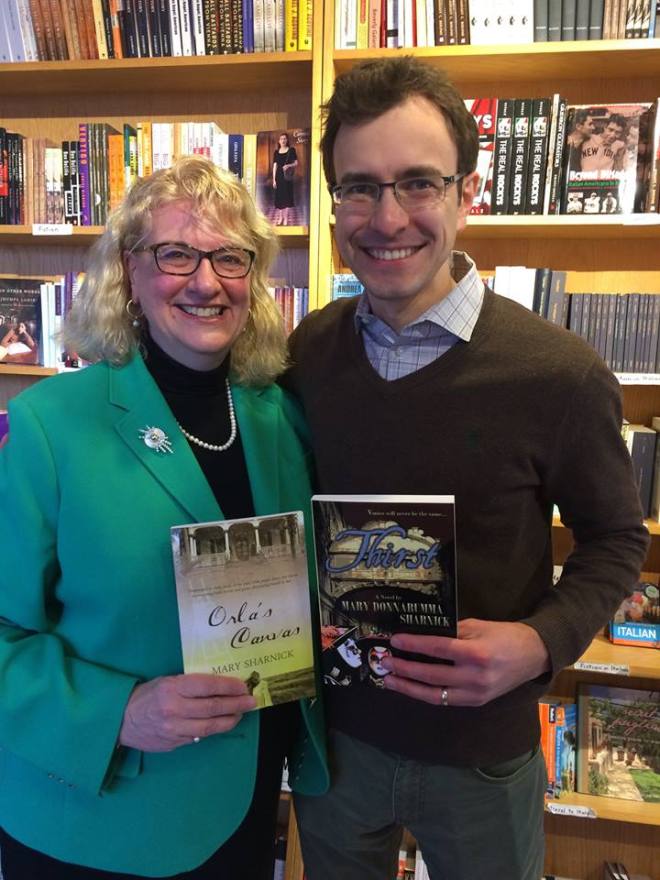

Congratulations to Mary Sharnick whose lyrical novel, Orla’s Canvas , has won the 2016 Connecticut Press Club Award for best adult fiction novel. For more information on this wonderful author, please visit our Featured Author post, and an Authors on Characters post about the creation of the character Orla.

Nicola Orichuia has founded a gem of a bookstore in Boston’s North End, right across from the Paul Revere House. He describes it as “an Italian American Cultural Hub.” And he hosts Italian-American authors like myself, offering us a place to share our craft with any and all interested.

Nicola Orichuia has founded a gem of a bookstore in Boston’s North End, right across from the Paul Revere House. He describes it as “an Italian American Cultural Hub.” And he hosts Italian-American authors like myself, offering us a place to share our craft with any and all interested.